Since the 2024 murder of Brian Thompson, the CEO of UnitedHealth Group’s insurance division, employers are reexamining their corporate security policies, which are designed to protect employees, including executives, from harm. The law is clear that the value of personal protection benefits provided to employees may be excluded from income under the working condition fringe benefit exclusion of Section 132(d) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended,1 provided the costs of the security would be deductible as ordinary and necessary business expenses under Section 162 by the employee if the employee were to pay for those costs directly.2 Moreover, since its issuance forty years ago, Treasury Regulations Section 1.132-5(m), a special valuation rule in the fringe benefit regulations applicable to working condition fringe benefits, excludes or reduces the value of certain fringe benefits provided to employees receiving personal protection when they are transported for personal purposes in company cars or on corporate aircraft. At the time the provision was drafted, domestic terrorism was not a constant fear, and the impact of the digital age on the proliferation of viable threats against executives would have been hard to imagine. Perhaps no other provision within the fringe benefits regulations is so outdated in its attempt to describe the realities of the modern world.

Even though the World Trade Center was bombed in 1993, years before the events of September 11, 2001, neither the Internal Revenue Service nor most Americans viewed the threat of terrorism as a significant risk when traveling within the United States. Likewise, the drafters of Treasury Regulations Section 1.132-5(m) in 1985 could not have contemplated how social media and the internet would one day create additional risks for public figures and other notable people. Consequently, heightened concern about the personal safety of employees has caused many employers to reexamine their corporate security policies. Realizing the risks that they may face even while in the United States, many corporate executives are now more open to accepting the full range of protective measures that security professionals have determined to be necessary. In conjunction with upgrading their security programs, employers may want to consider developing an overall security program that qualifies for the special valuation rules in the working condition fringe benefit regulations.

This article reviews the tax requirements applicable to nongovernmental employees when using employer-provided transportation for security reasons. If the employer’s security program meets these requirements, the value of any additional security protection provided to transport those employees with respect to whom a bona fide business-oriented security concern exists may be excluded from income under Section 132(d) of the Internal Revenue Code. Moreover, a special safe harbor rule for valuing flights on the corporate aircraft for security concerns permits the employer to value any personal flights at a rate that is generally more favorable than the rate provided under the rules used by companies to value flights on noncommercial aircraft.

Overview of Transportation-Related Security Rules

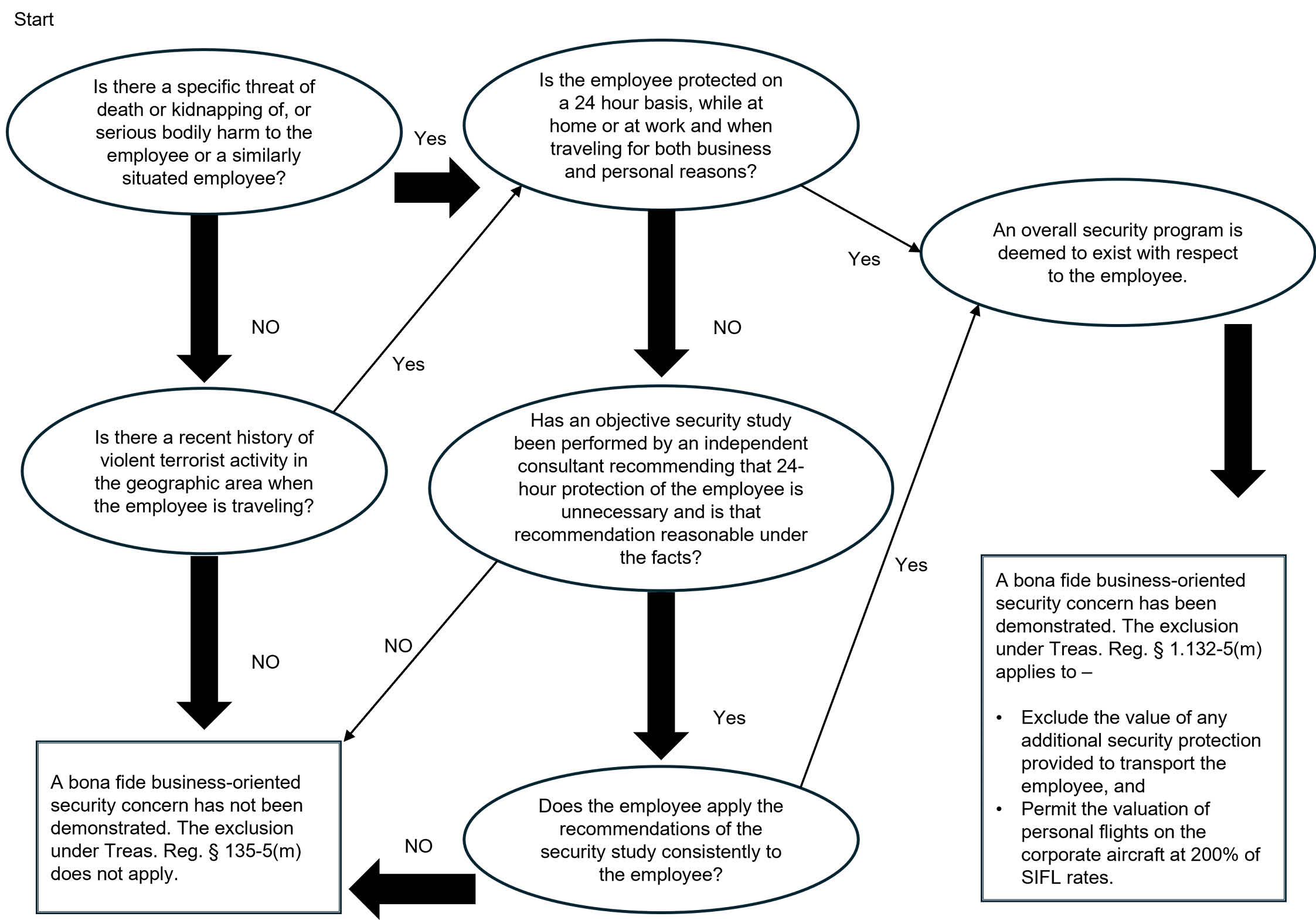

The working condition fringe benefit regulations3 permit employers to exclude from income a portion of the value of security protection provided to employees4 when transporting them for personal purposes in company cars or on corporate aircraft. To take advantage of these rules, the nongovernmental employer must prove that:

- a “bona fide business-oriented security concern” with respect to the employee exists at the time the security protection is provided; and

- if security protection is provided on a less-than-twenty-four-hour basis to the employee, the employer has obtained and consistently followed the recommendations of a study prepared by an independent security consultant who has objectively and reasonably assessed the type of security protection needed in each particular case.5

A “bona fide business-oriented security concern” exists only if the facts and circumstances establish a specific basis for concern regarding the employee’s safety. The examples given by the regulations are: 1) threats of death or kidnapping of, or serious bodily harm to, the employee receiving the protection or of a “similarly situated employee” or 2) a recent history of violent terrorist activity (such as bombings) in the geographic area in which the transportation is provided.6 In other words, the regulations contemplate a bona fide business-oriented security concern arising from specific threats to that employee’s or a similarly situated employee’s safety, as well as from the known existence of terrorist activity in the area in which the employee travels.

Establishment of an Overall Security Program

Even if the employer demonstrates a factual basis for concern regarding the employee’s safety, no bona fide business-oriented security concern will be deemed to exist unless the employer also demonstrates that an “overall security program” has been provided to protect the employee.7 This can be accomplished either by protecting the employee on a twenty-four-hour basis or by providing security according to the recommendations of an “independent security study.” Twenty-four-hour protection means that the employee must be protected while at home and at work and while traveling for both business and personal reasons (including commuting). The bodyguard/chauffeur must be trained in evasive driving techniques, and the car must be specifically equipped with security devices. Access to both the employee’s home and the workplace must be controlled through the use of guards, metal detectors, alarms, or similar devices. Finally, in appropriate cases, air travel should be on corporate aircraft for both business and personal purposes.8 Figure 1 spells out some considerations for determining whether a bona fide business-oriented security concern exists.

Independent Security Study

Because most executives reject the notion of living with twenty-four-hour protection, implementing an “independent security study” is usually the more viable alternative. For a study to qualify, it must satisfy the following conditions:

- The security study must be performed with respect to the employer and employee (or a similarly situated employee of the employer) by an independent security consultant;

- The security study must be based on an objective assessment of all facts and circumstances;

- The security study must determine that twenty-four-hour protection of the employee is not necessary, and the determination must be reasonable under the circumstances; and

- The employer must consistently apply the recommended security measures contained in the study to the employee.9

The regulations do not specify how an independent consultant should go about evaluating the employee’s need for security. The IRS has issued no other guidance on the security exclusion rules, not even in the form of private letter rulings or technical advice memoranda, which could provide insight into what the IRS might view as a sufficient evaluation. Before September 11, the IRS was adamant, in informal conversations, that there must be concrete proof of specific personal threats against the executive receiving protection. Thus, whenever possible, the study should refer to any specific threats received either by the executive who is the subject of the study or by similarly situated employees, because the regulations warn that a “generalized concern for an employee’s security” is not a bona fide security concern.10

In addition, by analogy to the special rule permitting government employers to conduct their own internal security studies in lieu of hiring an independent security consultant, any security study prepared for a private sector employer should include “an estimate of the length of time during which protection will be necessary.”11 In any event, an independent security study should include the following elements:

- A discussion of any specific personal threats against the executives covered by the study or any similarly situated employees;

- A discussion of the more general business-oriented security concerns facing the company’s executives. For example, the study may emphasize the increased danger that high-profile and high-net-worth individuals, particularly executives of multinational companies, face when traveling at home and abroad. It may also consider whether the company’s industry is likely to enflame passions among segments of the population that could result in specific risks. Certain industries, such as oil and gas, timber, and others have often engendered potentially violent activists even if their executives may not be household names. Conversely, the safety concern may be company-specific—as in the cases of manufacturers that have recently reduced their workforces or closed facilities—that could result in threats from disgruntled former employees;

- A discussion of the methods used by the security consultant to analyze the existence of security concerns for making recommendations. For example, the security consultant should interview each executive and survey his or her residence(s) to assess the level of current security and the enhancements needed. In addition, the security consultant should survey the corporate offices and the executive suite. If there is a corporate aircraft, the security consultant should assess the level of twenty-four-hour security at the hangar where the aircraft is kept;

- A discussion of the role of corporate security personnel in monitoring the protection of the covered executives;

- Recommendations for improving the company’s current security protection of the executives covered by the study or similarly situated employees. For example, the study may recommend that a chauffeur trained in evasive driving techniques be used to drive the executives between their residences and regular places of business. The study may provide recommendations concerning the enhancement of both home and workplace security. The study may also conclude that the executives should travel by corporate jet, whenever possible, and that personnel should be hired to guard the aircraft, particularly when it is grounded in a foreign country. Likewise, the study may recommend procedures for clearing all travel itineraries through the corporate security department, so that security personnel can provide travel advisory services in advance and arrange for additional ground security at the destination; and

- A determination whether twenty-four-hour protection of the executive is not warranted given the current security threat and protective measures to be implemented.

Applying the Security Study

With respect to any executive who receives twenty-four-hour security protection, the security-protection exclusion is not contingent on a security study prepared by an independent outside consultant. If the application of the security protection exclusion depends on a security study prepared by an independent consultant, however, the regulations require “the employer [to apply] the specific security recommendations contained in the security study to the employee on a consistent basis.”12 In addition, companies should request periodic updates of their security studies, especially when affected executives change their worksites or residences or both. Moreover, whether or not a new study is periodically obtained, each employer must “periodically evaluate the situation for purposes of determining whether the bona fide business-oriented security concern still exists.”13 Thus, any employer maintaining an overall security program should set a schedule to review whether the recommendations are being followed and to reevaluate the level of risk.

Valuation of Personal Travel

Cars and Chauffeurs

When the regulatory requirements for demonstrating a bona fide business-oriented security concern have been met, the value of “transportation-related security” may be excluded from the employee’s gross income as a working condition fringe benefit if, but for the bona fide business-oriented security concern, the employer would not have adopted those security measures. This does not mean that a primarily personal trip by the employee will be converted into an excludable fringe benefit. As explained by the regulations, only the value of the added security measures will qualify for exclusion as a working condition fringe benefit.

For example, if an employer provides an employee with a vehicle for commuting and, because of bona fide business-oriented security concerns, the vehicle is specially designed for security, then the employee may exclude from gross income the value of the special security design (for example, bulletproof glass) as a working condition fringe. The employee may not exclude the value of the commuting from income as a working condition fringe, because commuting is a nondeductible personal expense.14

Thus, the value of any personal use of an employer-provided vehicle must still be included in the employee’s gross income and treated as wages (and subject to payroll taxes). For example, if the employer values the personal use of the car using one of the special valuation rules, such as the automobile lease valuation rule,15 that calculation is not affected by the value of any security features added to the car following an overall security study, because the value of the personal use of the car must still be included in the employee’s income.

Likewise, in addition to being able to exclude from income the incremental value of the vehicle attributable to bulletproof glass or other security features, the employee will be able to exclude the entire value of the services of the bodyguard/chauffeur from his income. However, the bodyguard/chauffeur must also be trained in evasive driving techniques.16

Corporate Aircraft

Safe Harbor Valuation Rule for “Control Employees”

If the security study recommends that the covered executives use the corporate aircraft for both business and personal purposes, the employer is permitted to exclude the excess value, if any, of any personal trip computed under the noncommercial flight rule of Treasury Regulations Section 1.61-21(g) over the value computed under the special safe harbor valuation rule for flights required because of bona fide business-oriented security concerns.17 Specifically, the value of the safe harbor airfare is determined under the noncommercial flight valuation rule by multiplying 200 percent by the applicable cents-per-mile rates (commonly referred to as the standard industry fare level, or SIFL, rates) by the number of statute miles in the flight and then adding the applicable terminal charge. In most cases involving the use of corporate jets, this working condition fringe safe harbor for security-related travel reduces the valuation of personal trips on the corporate jet from 400 percent of the SIFL rates to 200 percent. The reason is that the aircraft multiples of the noncommercial flight valuation rule (for example, 400 percent of the SIFL rates) are based on the maximum certified takeoff weight of an aircraft. The multiples vary according to whether the employee is a “control” or “non-control” employee.18 Because most large corporate jets have a maximum takeoff weight of 25,001 pounds or more and executives are considered to be “control” employees for purposes of these rules, the aircraft multiple is usually 400 percent of the SIFL rates.19 Thus, when a personal flight on the corporate aircraft is provided for security reasons, the flight may be valued at the lower aircraft multiple of 200 percent, resulting in significant savings in employment taxes. The company may use a lower multiple for flights that qualify, such as when an executive uses a helicopter or light jet or if the company is providing corporate aircraft transportation to an employee who is not a control employee.

Valuation of Flights by Family Members

Equally favorable is the valuation rule for personal flights by family members traveling with the executive. If a bona fide business-oriented security concern exists with respect to an employee, the concern is deemed to exist with respect to the employee’s spouse and dependents when they fly with the employee. Therefore, their personal flights may be valued at 200 percent of the SIFL rates under the safe harbor valuation rule described above.20

If the spouse and dependent children of an employee covered by an independent security study travel on the corporate aircraft without the executive, however, a separate security threat must be shown and a separate independent security study must be obtained concerning the family members in order for their trips to be valued at the lower (200 percent of the SIFL) rate. Without a separate security study, personal trips by any family member flying separately from the executive must be valued using the special valuation rules generally applicable to such flights under the regulations, that is, at 400 percent of the SIFL rates.21

Risks Associated With Incorrect Use of Transportation-Related Security Rules

The IRS has never issued guidance concerning what if any penalty would apply if the agency successfully challenged the existence of a bona fide business-oriented concern or if it prevailed in its assertion that the recommendations of the security study were not applied consistently to covered employees. The fringe benefit regulations provide that, if a special valuation rule is not properly applied to a fringe benefit (or if part or all of the value of a flight is incorrectly excluded from income as a working condition fringe), the value of the fringe benefit may not be determined by reference to any value calculated under any special valuation rule in the regulations, but rather must be determined according to general valuation rules, that is, fair market value.22 In other words, the fringe benefit must be valued by the amount that an individual would have to pay for the particular fringe benefit in an arm’s-length transaction. Specifically, the value of a flight on an employer-provided aircraft would have to be determined by the cost to charter a comparable aircraft.23

Thus, were the IRS to challenge the employer’s use of the transportation-related security rules, it could argue that not only was the special safe harbor rule for security protection in Treasury Regulations Section 1.132-5(m) used incorrectly, but also that the underlying special valuation rule for noncommercial flights in Treasury Regulations Section l.61-21(g) was used incorrectly. In other words, the IRS could attempt to impose employment taxes on the difference between the charter value of the personal flights and the value determined by the employer using the safe harbor based on 200 percent of the SIFL rates. However, if the employer obtained an independent security study that concluded a security threat existed and evidence supports the employer’s good faith efforts to apply the recommendations in the study consistently, an argument exists that the maximum exposure to the employer, in the face of an IRS challenge, should be limited to the employment taxes on the difference in value for the flights computed using 400 percent of the SIFL rates (the value that would have ordinarily applied under the noncommercial flight valuation rule of Treasury Regulations Section 1.61-21(g)) and 200 percent of the SIFL rates.24 In addition, the employer would be liable for the employment taxes on the increased incremental value of any additional security measures provided in conjunction with ground transportation.

Non-Transportation Benefits

Although the final fringe benefit regulations, effective in 1989, require the use of home and workplace security measures combined with twenty-four-hour security, the regulations do not specify that home security systems (or even workplace security measures or bodyguards) are excludable as “working condition fringes” when such measures are recommended by an independent security study. The regulations focus on the exclusion applicable to vehicles, aircraft, and other “transportation-related security.”25 The pre-1989 temporary fringe benefit regulations, by contrast, stated that if a reasonable security study is adopted, “the value of security [impliedly, all security measures] provided pursuant to [such] a security study . . . may be excluded from income.”26 This is consistent with the legislative history, which explains that the security-protection exclusion was designed to cover any safety precautions provided by the employer that would be considered ordinary and necessary business expenses.27 Both the temporary and final regulations warn, however, that “no exclusion from income applies to security provided by the employer that is not recommended in the security study.” In context, though, it is clear that this statement refers to transportation-related security.

The final regulations contain an example that makes clear that non-transportation security fringes may be excludable, even if a bona fide business-oriented security concern does not exist, because the employer does not follow the recommendations of an independent security study.28 In example 5 of the final regulations, the employer provides security only for an executive’s commutes and not for other ground transportation, contrary to the recommendation of the independent security consultant. Nonetheless, the example acknowledges that the bodyguard who does not provide chauffeur or other personal services to the employee or his family may be excludable as a working condition fringe benefit under the general rules applicable to those types of fringe benefits.29

Even though the final regulations do not consider security protections other than transportation-related ones, it is logical to assume that home security systems should be excludable as working condition fringes during the period that protection of the employee is recommended by the independent security study due to the existence of a bona fide business-oriented security concern. If the executive is allowed to keep any home burglar alarm system or other security devices after termination of the security threat (or, if earlier, after termination of employment), it would be advisable to include in the employee’s wages the fair market value of the system at that time.30

Applying the transportation-related security rules, particularly with respect to travel on corporate aircraft, can drastically reduce the amount of income that executives must recognize in the case of employer-provided travel benefits. To take advantage of these rules, nongovernmental employers must demonstrate the existence of bona fide business-oriented security concerns with respect to the employees being protected and the implementation and consistent application of an overall security program to protect them. In light of recent events, employers are justly concerned about the safety of their employees and in establishing appropriate security programs.

S. Michael Chittenden is of counsel to the law firm Covington & Burling. He specializes in the areas of tax and employee benefits, with a focus on the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, information reporting and withholding, payroll taxes, and fringe benefits.

Endnotes

- The Treasury Regulations are set forth in 26 CFR Section 1, et seq. All references in this article to “Section” refer to the Internal Revenue Code.

- Treasury Regulations Section 1.132-5(a)(1).

- See generally Treasury Regulations Section 1.132-5(m).

- The term “employee” for this purpose includes common law and statutory employees, directors, independent contractors, and partners of partnerships. Treasury Regulations Section 1.132-1(6)(2).

- Treasury Regulations Section 1.132-5(m)(2). In 1992, the security protection rules were amended to permit government employers providing less than twenty-four-hour protection of their employees to prove the existence of an overall security program with a security study conducted by personnel expressly designated by the government employer, rather than hiring an outside consultant. No correlative change was made in the rules applicable to private sector employers. See Treasury Decision 8457, 57 Federal Register 62192 (December 30, 1992).

- Treasury Regulations Section 1.132-5(m)(2)(i). The security exclusion is available for either in-kind employer-provided security protection or cash reimbursements for the cost of that protection, provided that in the case of a cash reimbursement the employee verifies that the payment is actually used to purchase security protection, and any unused portion of the advance is returned to the employer. See Treasury Regulations Section 1.132-5(a)(l)(v).

- Treasury Regulations Section 1.132-5(m)(2)(ii).

- Treasury Regulations Section 1.132-5(m)(2)(iii).

- Treasury Regulations Section 1.132-5(m)(2)(iv).

- Treasury Regulations Section 1.132-5(m)(2)(i).

- Treasury Regulations Section 1.132-5(m)(2)(v)(B).

- Treasury Regulations Section 1.132-5(m)(2)(iv)(D).

- Treasury Regulations Section 1.132-5(m)(2)(i), as amended by Treasury Decision 8457, 57 Federal Register 62192 (December 30, 1992).

- Treasury Regulations Section 1.132-5(m)(l).

- Treasury Regulations Section 1.61-2l(d). Under the automobile lease valuation rule, the employee would be taxed only on 1) their percentage of the personal use of the vehicle times the “annual lease value” of the vehicle determined under the special tables in Treasury Regulations Section 1.61-21(d)(2)(iii), plus 2) the fair market value of any employer-provided gasoline for all personal miles driven (or ridden) in the vehicle.

- Treasury Regulations Section 1.132-5(m)(5).

- Treasury Regulations Section 1.132-5(m)(4).

- Treasury Regulations Section 1.61-21(g)(7).

- Treasury Regulations Section 1.61-21(g)(8)(i).

- Treasury Regulations Sections 1.132-5(m)(3)(i) and (ii).

- Treasury Regulations Section 1.132-5(m)(3)(iii).

- See Treasury Regulations Sections 1.61-21 (c)(5) and 1.61-21(g)(13)(ii).

- Treasury Regulations Section 1.61-21(b). In Technical Advice Memorandum 9801002 (September 3, 1997), the IRS relied on the regulation to rule that a car dealership was not entitled to use the automobile lease valuation rule in Treasury Regulations Section 1.61-21(d) for purposes of valuing the personal use of vehicles provided to employees, because the dealer had used an unauthorized method in valuing the vehicles. Consequently, the IRS assessed employment taxes on unreported income and wages based on the fair market value of the benefits. Likewise, in BMW of North America, Inc. v. United States, 39 F. Supp.2d 445 (D.N.J. 1998), the court held that Treasury Regulations Section 1.61-21(c)(5) was a penalty provision that applied when the taxpayer had used an incorrect valuation method to value the use of BMWs provided to employees of a dealership. Although TAM 9801002 and BMW of North America deal with the car valuation rules, the same approach would have theoretically applied to a case in which the IRS determined the SIFL rules were misused for valuing personal flights. Subsequent changes to the regulations in 1992 suggest that the IRS’ position in BMW may no longer be good law.

- Since the 2004 enactment of Section 274(e)(2) to limit the deductibility of aircraft expenses for “entertainment” flights by specified individuals, the use of the lower valuation based on 200 percent of SIFL, as permitted by Treasury Regulations Section 1.132-5(m)(4), has resulted in a greater deduction disallowance for personal flights that are considered to be for entertainment purposes.

- See Treasury Regulations Section 1.132-5(m)(2)(iv).

- See Treasury Regulations Section 1.132-5T(m)(2)(iv).

- Rept. No. 98-432, Part 2, 98th Congress, Second Session 1602 (1984). This concept is related to the rule allowing a deduction under Section 162 (and therefore an exclusion under Section 132(d)) for the cost of meals, entertainment, and similar personal items, which are not incurred while on business travel away from home overnight but are nevertheless clearly shown to be “different from or in excess of that which would have been [spent] for the taxpayer’s personal expense.” See Sutter v. Commissioner, 21 Tax Court 170 (1953), acq. 1954-1 CB 6; and Technical Advice Memorandum 80006004 (October 26, 1979).

- Treasury Regulations Section 1.132-5(m)(8), example 5 (value of services of bodyguard with professional security training excludable from employee’s income, even though an overall security study was not in existence).

- This example reflects, perhaps begrudgingly, the Tax Court’s decision in Est. of Frederick Cecil Bartholomew, 4 Tax Court 349 (1944), in which the services of a chauffeur/bodyguard attributable to protecting a child actor were held to be deductible under the predecessor to Section 162.

- The fair market value of the system or devices, as determined at the time inclusion in wages is required, is likely to be less than the original value at the time of installation.